Cultivating Self-Awareness: The Hidden Engine of Psychophysical Health & Peak Performance

- Sep 22, 2025

- 6 min read

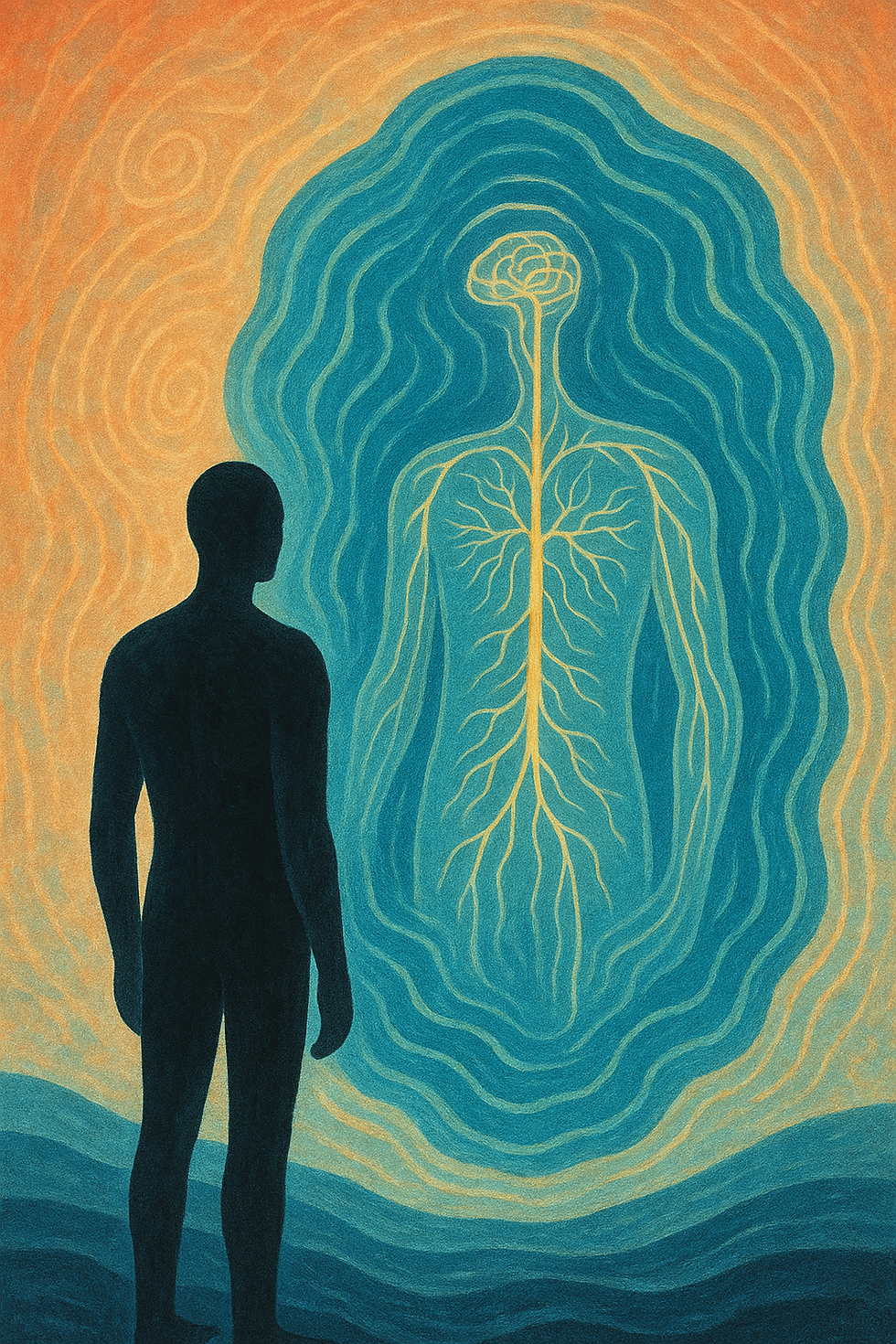

Most of us look in the mirror daily. We adjust hair, check posture, maybe even measure progress toward a physical goal. There’s another kind of reflection though that’s often ignored, and it matters even more for health and performance. It’s the engine behind self-awareness: the ability to notice, interpret, and respond to our internal states.

At first glance, self-awareness sounds a bit nebulous, something more at home in a mindfulness retreat than in sports science or performance psychology, but research suggests it’s as biological as it is contemplative. The capacity to “tune in” determines whether we burn out or bounce back and plateau or progress. Self-awareness is less about endlessly analyzing ourselves and more about cultivating the skill of noticing, without judgment, what the body and mind are already saying.

What Do We Mean by Self-Awareness?

Self-awareness in psychophysical health is the ability to recognize signals from both mind and body and to act in alignment with them. It’s noticing the elevated heart rate before a big presentation, the creeping irritability after a sleepless night, or the subtle shift in breathing that precedes fatigue.

In neuroscience, this overlaps with interoception, which is the brain’s mapping of internal sensations such as heartbeat, hunger, or muscle tension. Regions like the insula and anterior cingulate cortex act like a dashboard, constantly sampling signals from within and translating them into feelings we can act on.

Think of it as the body’s internal language. Self-awareness is learning to read fluently. Without it, we’re like drivers ignoring the “check engine” light and pressing the gas harder until the system quietly falls apart.

Self-awareness isn’t self-obsession. It’s the skill of interpreting biological feedback before the system forces us to stop.

Why Does Awareness Feel So Hard?

If tuning in is so important, why do so many of us struggle? The tricky part is that modern life drowns signal in noise. Constant notifications, deadlines, and stimulants blunt our ability to distinguish between “I’m genuinely tired” and “I just need another coffee.”

Physiologically, chronic stress plays a major role too. Elevated cortisol narrows attention toward external threats, which made sense when predators lurked outside the cave, but in a boardroom or on the training ground, it means we miss quieter cues from within. We barrel past subtle signs until the body speaks in louder, less convenient ways like injury, illness, or burnout.

This is why so many athletes describe injuries as “coming out of nowhere” even though micro-signals were there for weeks or why professionals wake up one morning feeling inexplicably exhausted, not realizing their nervous system has been running on emergency mode for months.

The irony? Self-awareness isn’t about acquiring new information. It’s about rediscovering what’s always been there, beneath the static.

The Biology of Knowing Ourselves

When self-awareness is strong, the body operates like the finely tuned machine it’s meant to be, with each piece in sync and rising to match the tempo and intensity of our lives. When it’s weak, the different pieces of our lives tend to compete with each other, leading to inefficiencies and eventual breakdown to force a reset.

At the biological level, awareness improves regulation. Studies show that individuals with higher interoceptive accuracy, for example, those who can accurately count their heartbeat without touching their pulse, are better at emotional regulation and stress resilience. Their autonomic nervous system balances more efficiently between sympathetic (activation) and parasympathetic (recovery) states.

Hormones follow suit. Greater awareness is linked with healthier cortisol rhythms, steadier glucose regulation, and more efficient cardiovascular responses. In plain terms, knowing ourselves isn’t just “mental hygiene.” It’s a survival advantage coded into physiology.

At the end of the day, self-awareness is measurable biology that shapes how well our system adapts to strain.

Performance Without Awareness

Picture two athletes. Both train equally hard. Both follow structured programs. Only one listens closely to subtle cues, such as the heaviness in their legs, the irritability after poor sleep, or the spark of focus when nutrition is dialed in. The other pushes blindly, ignoring these whispers until the system rebels.

The difference over time is profound. The aware athlete adapts sustainably, cycling effort and recovery in ways that strengthen long-term performance. The unaware athlete may spike faster but crashes sooner, battling recurring injuries, stagnation, or burnout.

Outside of sport, the same applies to work and creativity. Self-awareness determines whether we mislabel cognitive fatigue as laziness or recognize it as the brain’s biological need for reset. It’s the hinge between interpreting struggle as personal failure versus adaptive feedback.

The cost of lacking awareness isn’t just inefficiency. It’s self-sabotage disguised as discipline.

How Awareness Shapes Identity

Here’s where psychology meets biology. Awareness changes not only what we do, but who we believe ourselves to be.

When we recognize patterns, say, that anxiety spikes after three nights of poor sleep, we shift from “something’s wrong with me” to “this is how my system operates.” That reframe helps us establish a more robust relationship with ourselves. It allows us to see struggle not as brokenness but as a signal.

Over time, this cultivates self-trust. Athletes who learn to read their bodies stop fearing setbacks. Professionals who know their rhythms stop over-interpreting lapses in focus. Parents who notice emotional strain early intervene before snapping at loved ones.

In this way, self-awareness isn’t just a tool. It’s an anchor of identity. We stop being at the mercy of invisible systems and start partnering with them to steer our lives in the direction we want to go.

Practical Self-Awareness Without Overthinking

The concern many have is that “tuning in” will lead to too much self-focus and not enough action. The truth is much simpler: effective awareness is brief, consistent, and actually improves our ability to react.

One proven method to improve self-awareness is micro-check-ins. These are 30-second pauses to notice three things: breath, body tension, and emotional landscape. Over time, these snapshots build a reliable map of internal states, allowing adjustments before breakdown.

Another approach, which we’ve mentioned before, is structured reflection. All it takes is us writing down daily observations about energy, mood, or performance alongside concrete factors like sleep or nutrition, more of just recording a stream of consciousness to free what’s locked in our heads. This externalizes data that otherwise feels vague, revealing patterns we would have missed otherwise.

Perhaps the most overlooked tool is social awareness as self-awareness. Trusted teammates, friends, or partners often notice shifts we ignore. Asking for their perspective expands our internal mirror.

Working on this kind of awareness doesn’t require an hour-long meditation. It’s about building a feedback loop between body signals and daily decisions.

From Awareness to Adaptation

Awareness alone doesn’t guarantee change. The power lies in pairing recognition with action. If the mirror shows fatigue, the next step is rest. If it reveals calm, the step may be to lean into challenge.

Biologically, this is how resilience is built. Stress applied, signals noticed, recovery engaged. Each cycle deepens the system’s adaptability. Without awareness, stress piles up unmodulated, but with it, stress becomes training.

Performance health, then, is less about chasing perfection and more about refining the radar we use to navigate. Awareness doesn’t eliminate strain. It transforms it into growth.

Reframing

The core truth is this: we are not fragile for feeling tired, stressed, or off. We are adaptive. Those signals are proof that our system is working, communicating, and recalibrating.

Self-awareness is about reframing stress. It’s about listening well enough to struggle wisely. When we do, strain becomes feedback, setbacks become information, and health becomes less about control and more about partnership with our own biology.

The mirror inside doesn’t always show what we want, but it always shows what we need.

References

Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666.

Critchley, H. D., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2017). Interoception and emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 7–14.

Mehling, W. E., et al. (2012). Body awareness: a phenomenological inquiry into the common ground of mind–body therapies. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 7(1), 6.

Farb, N. A., Segal, Z. V., & Anderson, A. K. (2013). Mindfulness meditation training alters cortical representations of interoceptive attention. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 15–26.

Khalsa, S. S., et al. (2018). Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513.